Introduction: The Moral Awakening of Machines

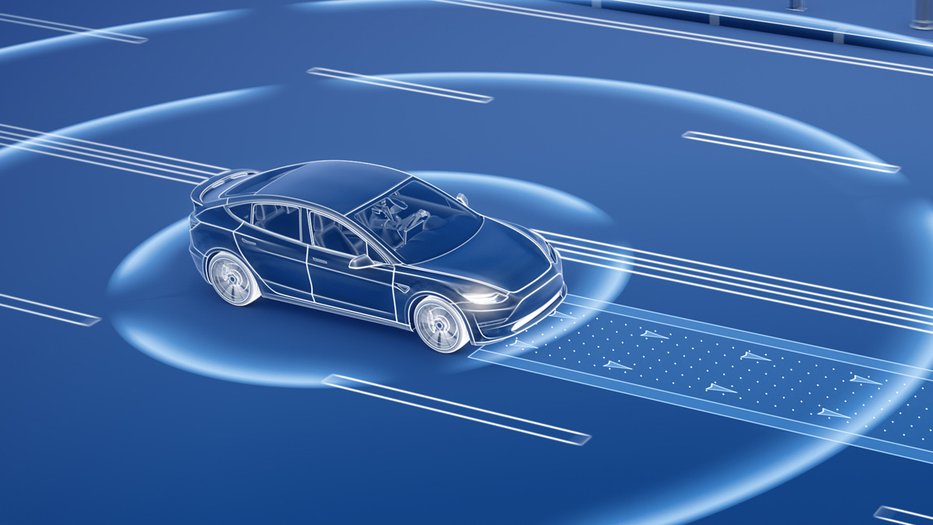

The emergence of autonomous systems represents not only a technological milestone but also a profound moral turning point. For the first time in human history, we are designing entities capable of making decisions without direct human input—machines that perceive, reason, and act within complex social environments. Whether it’s a self-driving car choosing between two collision scenarios, an autonomous drone executing a mission, or an AI managing medical diagnostics, each decision carries ethical weight.

As artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics progress toward higher autonomy, traditional governance frameworks—built around human accountability—begin to strain. How should we assign moral and legal responsibility to non-human agents? Who decides the “values” embedded in their algorithms? And how can societies ensure that technological progress aligns with human rights, justice, and dignity?

This essay explores the ethical and governance challenges posed by autonomous systems. It integrates philosophy, law, and public policy to examine how humanity can build a future in which autonomy enhances, rather than undermines, our collective well-being.

1. Understanding Autonomy: From Human Choice to Machine Agency

1.1 Defining Autonomy

In philosophy, autonomy refers to the capacity for self-governance—the ability to act according to one’s own principles rather than external compulsion. When applied to machines, autonomy signifies the ability to perform tasks, make decisions, and adapt to new circumstances without direct human intervention.

However, machine autonomy differs fundamentally from human autonomy. Humans act from intention and consciousness, whereas machines act from programmed objectives and probabilistic models. The ethical tension arises precisely here: we are imbuing artificial entities with agency-like behavior, but without the moral awareness that typically accompanies it.

1.2 From Automation to Moral Machines

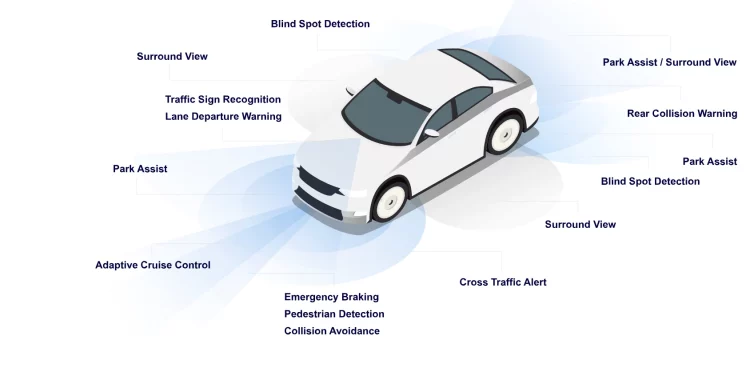

Earlier generations of machines followed strict instructions—performing repetitive tasks with no deviation. Autonomous systems, by contrast, navigate uncertainty. A self-driving vehicle must choose when to brake or swerve; a military drone may assess whether to engage a target. These are not mere technical calculations—they are moral ones, encoded in software.

The question is no longer whether machines can make decisions—they already do—but whether they should, and under what ethical constraints.

2. The Foundations of Machine Ethics

2.1 Consequentialism and Utilitarian Design

Many autonomous systems today operate on utilitarian logic: maximize overall benefit while minimizing harm. For instance, collision-avoidance algorithms in self-driving cars often calculate which action leads to the fewest casualties. This echoes the utilitarian principle articulated by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill: “the greatest good for the greatest number.”

Yet, moral philosophers have long warned against the simplicity of such logic. What if saving more lives means sacrificing a child over an adult? Or prioritizing passengers over pedestrians? The challenge lies in translating ethical nuance into computational logic.

2.2 Deontology and Rule-Based Ethics

An alternative is deontological ethics, championed by Immanuel Kant, which emphasizes moral duties over outcomes. A deontological machine might refuse to take any action that directly harms a human, regardless of utility. However, rigid rule-based ethics may fail in dynamic real-world situations where every option involves some harm.

2.3 Virtue Ethics and Contextual Judgment

Recent research advocates for “virtue-based” AI—systems designed not just to follow rules or optimize outcomes, but to act according to socially desirable traits such as empathy, fairness, and prudence. This requires machine-learning systems that continuously evolve ethical understanding based on social context—a formidable challenge, but one that reflects how human morality actually works.

3. The Problem of Responsibility: Who Is to Blame?

3.1 The Black Box of Accountability

Autonomous systems complicate traditional notions of responsibility. In human-operated contexts, blame can be assigned to a driver, pilot, or operator. But when a self-driving car crashes due to an algorithmic error, who is responsible—the manufacturer, the software developer, the data supplier, or the AI itself?

The opacity of deep learning models—often described as “black boxes”—further clouds accountability. Without transparent reasoning, it becomes nearly impossible to trace why a system acted the way it did.

3.2 Distributed Responsibility

Some scholars propose a “distributed responsibility model,” recognizing that accountability in autonomous systems is collective. Designers, regulators, and users all contribute to system outcomes. Legal scholars are now exploring new frameworks like algorithmic liability and shared accountability to address these multi-agent complexities.

3.3 The Legal Personhood Debate

A controversial question is whether autonomous systems should be granted legal personhood, similar to corporations. The European Parliament briefly entertained this idea in 2017, suggesting “electronic personality” status for advanced robots. Critics argue this could allow companies to evade liability by shifting blame to machines. Proponents counter that legal personhood might be necessary for systems that act independently and own data or assets.

4. Data, Bias, and Algorithmic Justice

4.1 Bias as a Mirror of Society

Autonomous systems are only as fair as the data that trains them. Biased datasets—reflecting historical inequalities in race, gender, or class—can lead to discriminatory outcomes. Facial recognition systems, for example, have shown significantly higher error rates for women and people of color, leading to wrongful arrests and surveillance abuses.

4.2 Algorithmic Transparency and Explainability

To counter these risks, scholars advocate for explainable AI (XAI)—systems capable of articulating the reasoning behind their decisions. Transparency is not merely a technical goal but a democratic one; it enables citizens, regulators, and affected individuals to challenge decisions made by algorithms.

4.3 Ethics of Data Ownership

Autonomous systems depend on vast quantities of user data. But who owns this data—the individual, the company, or the machine? Emerging proposals like data trusts and data dividends aim to redistribute the economic and ethical value of personal data, ensuring users retain agency over their digital selves.

5. Governance Frameworks: From Regulation to Co-Evolution

5.1 Regulatory Landscape

Different regions are developing distinct governance models for autonomous systems.

- The European Union has taken a precautionary, human-rights-based approach through its AI Act, classifying systems by risk and mandating transparency.

- The United States emphasizes innovation and self-regulation, relying on industry guidelines and liability laws.

- China pursues state-driven governance, integrating AI into national development strategies while maintaining strict data control.

This divergence reflects deeper cultural values—privacy, collective welfare, and trust in institutions.

5.2 Dynamic Regulation

Static laws struggle to keep pace with rapidly evolving technology. Hence, “dynamic regulation” is emerging as a new paradigm—adaptive legal frameworks that evolve alongside technological progress. This includes regulatory sandboxes, where companies can test autonomous systems under supervised, flexible conditions.

5.3 Global Coordination

Autonomous systems transcend borders—data flows and drones do not stop at national boundaries. Therefore, global governance mechanisms are essential. Organizations like the OECD and UNESCO are developing international principles emphasizing fairness, accountability, and transparency in AI.

6. Military Autonomy and the Ethics of Lethal AI

6.1 Autonomous Weapons Systems (AWS)

Perhaps the most controversial application of autonomy is in warfare. Autonomous weapons systems—capable of selecting and engaging targets without human intervention—pose existential ethical questions. The debate centers on whether such systems can comply with international humanitarian law and whether delegating lethal force to machines is morally permissible.

6.2 Meaningful Human Control

The concept of meaningful human control has become a central principle in global arms discussions. It asserts that humans must retain ultimate authority over life-and-death decisions. Yet, as systems become faster and more complex, maintaining real-time human oversight becomes increasingly difficult.

6.3 Calls for a Ban

Over 30 countries and hundreds of AI researchers have called for an international treaty banning fully autonomous weapons. However, major military powers remain reluctant, fearing strategic disadvantage. The outcome of this debate will shape the moral trajectory of 21st-century warfare.

7. Building Ethical Autonomous Systems

7.1 Ethics by Design

Embedding ethics into technology requires proactive design choices. “Ethics by design” advocates integrating moral reasoning, transparency, and accountability into every stage of system development—from data collection to algorithmic decision-making.

7.2 Participatory Governance

Democratizing AI governance means involving diverse stakeholders: engineers, policymakers, philosophers, and the public. Citizens should have a voice in defining what values autonomous systems embody, ensuring they reflect cultural pluralism rather than technocratic elites.

7.3 Education and Ethical Literacy

Just as engineers learn mathematics, they must also learn moral reasoning. Ethics should be integral to AI and robotics education, fostering a generation of technologists who see moral reflection as essential to innovation.

8. The Future of Governance: Toward Human–Machine Symbiosis

8.1 From Control to Collaboration

Rather than framing governance as control over machines, the next phase envisions collaboration with them. Autonomous systems could help monitor ethical compliance, flag bias, or even assist policymakers in drafting regulations—ethics guided by both human and machine intelligence.

8.2 Cultural Diversity in Machine Morality

There is no universal moral code. Western individualism, Confucian collectivism, and African communalism all define ethics differently. As AI spreads globally, machine ethics must respect moral diversity while upholding universal human rights—a delicate balance that will define the next century of AI governance.

8.3 The Horizon of Moral Coevolution

Ultimately, ethics and technology evolve together. Just as industrialization gave rise to labor laws and environmental ethics, the age of autonomy will inspire new moral frameworks. The challenge is not to make machines human, but to make humans more humane through their interaction with machines.

Conclusion: The Moral Compass of the Autonomous Age

Autonomous intelligence forces humanity to confront its deepest philosophical questions—about agency, responsibility, and the meaning of moral action. Machines reflect the values of their creators; thus, the ethics of AI is ultimately a mirror of our own society.

If guided by wisdom, transparency, and compassion, autonomous systems can amplify human potential and reduce suffering. But if left unchecked, they could entrench inequality, erode privacy, and desensitize us to moral judgment.

Governance in the autonomous age is therefore not merely a legal or technical task—it is a moral imperative.

We are not just building intelligent machines; we are building the ethical architecture of the future. The true measure of progress will not be how autonomous our systems become, but how responsibly we choose to live alongside them.