Introduction: The Dawn of the Aerial Metropolis

The 21st century marks an inflection point in how cities are imagined, built, and lived in. While the past century saw the vertical rise of skyscrapers as symbols of progress, the next era will witness the horizontal expansion of mobility into the sky. Urban Air Mobility (UAM) — the integration of aerial transportation systems into urban ecosystems — is no longer a futuristic dream. It is rapidly becoming an inevitable next phase of urban evolution.

From flying taxis to aerial delivery drones, UAM promises to revolutionize how people and goods move across congested cities. Yet, beyond its technological marvels lies a more complex question: How will UAM reshape society, economies, and the environment?

This essay explores the multidimensional impacts of UAM, focusing on three central domains — social transformation, economic disruption, and environmental sustainability. Through this lens, we can better understand how flying cities might redefine human experience, equity, and urban design in the coming decades.

1. The Social Dimension: Reimagining Urban Life Above Ground

Urban Air Mobility will not simply introduce a new transportation layer — it will alter how humans perceive proximity, community, and accessibility.

1.1 Mobility and the Redefinition of Distance

In traditional cities, distance is a function of ground traffic, congestion, and infrastructure. With UAM, distance becomes elastic. Commuting that once took an hour could take 10 minutes. The city becomes “compressed,” where previously disconnected neighborhoods now fall within a few minutes’ reach.

This temporal compression may redesign social and economic interactions, making the entire city function more like a single interconnected organism. It could foster inclusivity by connecting remote districts to central zones — or, conversely, deepen divisions if access remains restricted to the affluent.

1.2 Social Stratification and Accessibility

History teaches us that new technologies often begin as luxuries before becoming public goods. UAM’s early adopters are likely to be business travelers, high-income commuters, or emergency services. As economies of scale develop, however, costs will fall, and UAM could become a shared, accessible utility much like ride-hailing platforms did in the 2010s.

Yet, there remains a risk of “sky inequality” — where wealthier citizens dominate aerial routes while others remain ground-bound. Governments and city planners must therefore design policies ensuring equitable access to aerial mobility, perhaps through public UAM systems or integrated multimodal transport subsidies.

1.3 Psychological and Cultural Shifts

Beyond logistics, UAM will influence human psychology and culture. The idea of flying through cities invokes both excitement and anxiety. For some, it embodies freedom and innovation; for others, it evokes fears of surveillance, noise, and safety risks. Urban dwellers will need time to adapt their perceptions of privacy and spatial security in a world where skies are alive with motion.

2. Economic Impacts: The New Sky Economy

Urban Air Mobility is poised to create an entirely new economic ecosystem — a Sky Economy — encompassing manufacturing, services, infrastructure, and digital platforms.

2.1 Job Creation and Industry Growth

According to studies by NASA and Deloitte, UAM could generate hundreds of thousands of jobs globally by 2040, spanning pilot operations, aircraft manufacturing, software development, vertiport construction, and air traffic management. Entirely new sectors such as airborne logistics and on-demand aerial services will emerge, similar to how the smartphone revolution spawned app-based economies.

Moreover, traditional sectors — tourism, real estate, and healthcare — will benefit from improved mobility. Air ambulances could reach accident sites faster; tourism agencies could offer panoramic aerial tours; and property developers might market “sky access” as a premium amenity.

2.2 Investment and Urban Infrastructure Transformation

The development of UAM requires massive capital investment. Companies like Joby, Lilium, and Archer have already attracted billions in funding, signaling strong investor confidence. However, the real transformation will occur when cities integrate UAM into their master plans, redesigning rooftops and transport hubs as vertiport networks.

These infrastructure investments could revitalize urban peripheries, turning underused industrial zones into aerial mobility hubs and triggering secondary economic booms — from retail to hospitality around vertiport nodes.

2.3 Economic Disruption and Labor Displacement

Every technological revolution comes with displacement. UAM may reduce dependence on traditional taxi, bus, or short-haul air routes. Pilots and ground operators may face automation-driven redundancy as AI-guided aircraft become prevalent. Policymakers will need to anticipate these disruptions through reskilling programs and transition support, ensuring that the benefits of UAM do not come at the cost of widespread labor inequality.

3. Environmental Consequences: Flying Toward Sustainability

While Urban Air Mobility promises efficiency, its environmental impact remains a double-edged sword. Done right, it can contribute to a greener future; done poorly, it could compound existing sustainability challenges.

3.1 The Promise of Electrification

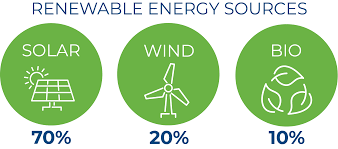

UAM is inherently tied to electric propulsion. eVTOLs eliminate direct emissions and can drastically reduce noise pollution compared to helicopters. If powered by renewable energy, the system could align with global carbon neutrality goals.

Moreover, aerial mobility can reduce surface congestion, lowering emissions from idling vehicles in dense traffic zones. A fully electrified air mobility network, integrated with renewable urban grids, could serve as a symbol of clean technological progress.

3.2 The Hidden Environmental Costs

However, the environmental equation is complex. The production of batteries involves intensive mining of lithium, cobalt, and nickel — all of which have ecological and ethical implications. Furthermore, large-scale charging demands may strain urban power grids if renewable sources lag behind adoption rates.

Aircraft noise, while reduced, remains nontrivial; the cumulative effect of thousands of small aircraft buzzing above cities could reshape urban soundscapes, requiring advanced acoustic management systems.

3.3 Urban Design for Eco-Integration

To mitigate these challenges, cities must approach UAM as part of a holistic sustainability strategy. Vertiports can be designed with solar rooftops, rainwater collection, and vertical gardens. Smart energy storage systems can balance loads between charging cycles and residential needs. The key lies in eco-synergistic design, where technological innovation complements — rather than competes with — natural systems.

4. Governance and Policy: Balancing Innovation with Public Good

The socio-economic success of UAM will depend on how effectively governance structures evolve to manage it.

4.1 Regulatory Readiness

Airspace management must be redefined for low-altitude, high-density flight. Governments must balance innovation incentives with public safety and privacy protection. Global aviation bodies like the ICAO and regional regulators such as the FAA are already testing new frameworks for low-altitude air traffic control.

Crucially, data privacy will become an essential legal concern — aerial systems equipped with cameras and sensors will constantly collect urban data, raising questions of surveillance, ownership, and consent.

4.2 Public–Private Partnerships

Successful UAM deployment requires cross-sector collaboration. Governments must partner with industry leaders, academia, and local communities. Public–private partnerships can accelerate research, fund infrastructure, and establish shared standards — preventing fragmented systems that could lead to operational chaos.

4.3 Ethical and Equity Considerations

UAM must be guided by ethical frameworks emphasizing fairness, accessibility, and inclusivity. Without careful planning, UAM could widen mobility divides. Cities should explore tiered pricing, public service integration, and universal access mandates to ensure that aerial transport benefits society at large.

5. Cultural and Urban Identity in the Age of Flight

As aerial mobility becomes part of daily life, it will transform not only how cities function but also how they are perceived.

5.1 Architectural Aesthetics

The skyline — once defined by static buildings — will become kinetic. Architects may design buildings with aerial docking bays and flowing forms optimized for air circulation. Rooftops will transition from passive spaces to active gateways, blurring the boundary between architecture and transportation.

5.2 Urban Psychology

Cities that embrace the sky will also redefine human psychology. The act of flying above one’s own city changes perspective — physically and emotionally. People may develop new forms of spatial identity, seeing their cities not just from the street but from above, reawakening the sense of wonder long lost in urban routine.

5.3 Cultural Imagination

Flying cities may become cultural icons — symbols of modernity, freedom, and environmental responsibility. Literature, cinema, and design will evolve to reflect this new relationship with the sky. Just as the automobile reshaped 20th-century culture, aerial mobility could inspire the aesthetic and symbolic narratives of the 21st.

6. A Vision for 2050: The Symbiotic City

By 2050, the integration of UAM could lead to symbiotic cities — dynamic ecosystems where air and ground mobility function as one. Imagine a morning where you order an eVTOL through an app, board from a rooftop vertiport, and land near your office within minutes. Packages, medical supplies, and emergency responders move seamlessly through the air, supported by renewable energy grids and real-time traffic algorithms.

In this future, time, energy, and space are optimized not through expansion but through coordination. The city becomes not a place of congestion, but a system of fluid movement — a living organism sustained by data, wind, and electric charge.

Conclusion: The Sky as the New Urban Frontier

Urban Air Mobility holds the potential to revolutionize urban living — not just by lifting people into the sky but by lifting societies into new paradigms of connection, equity, and sustainability.

Its social promise lies in accessibility and inclusiveness; its economic strength in innovation and efficiency; its environmental hope in electrification and green design. Yet, realizing this vision requires foresight, governance, and collective responsibility.

Flying cities are not distant science fiction — they are emerging before our eyes. The question is not whether humanity will take to the skies, but how wisely and equitably we will inhabit them.

The aerial age of cities is upon us, and with it, the challenge of designing not just flight paths, but a moral and sustainable architecture for the skies.