Introduction: A City That Lifts Off

Cities have always been defined by their ground-based infrastructures—streets, railways, and the invisible grids of utilities and data. Yet as the 21st century progresses, a quiet revolution is beginning above the rooftops: Urban Air Mobility (UAM). No longer the stuff of science fiction, aerial transport systems are emerging as a serious response to the congestion, pollution, and inefficiency of terrestrial travel. But what happens to a city when it gains a third dimension of movement? What does it mean for architecture, for social equity, for human psychology? This essay argues that UAM is not merely a transportation innovation; it is a profound transformation of how we inhabit, perceive, and organize urban space.

I. From Two-Dimensional Urbanism to the Vertical City

Traditional cities evolved around horizontal flow. The design of boulevards, the zoning of districts, and the clustering of economic centers have always depended on ground-level accessibility. Yet skyscrapers, drones, and air corridors now hint at a new spatial order.

Urban Air Mobility challenges the 2D paradigm by adding altitude as a civic dimension. Instead of being constrained by road grids, UAM vehicles—electric vertical takeoff and landing aircraft (eVTOLs)—can traverse cities using designated aerial corridors. This verticality demands a rethinking of city planning principles.

Architects and urban designers must now consider “aerial zoning”—the organization of air routes at varying altitudes, with landing pads or “vertiports” integrated into rooftops, parking structures, and transportation hubs. As these nodes proliferate, we may witness a new architectural typology: the “air-integrated building.”

In this vertical city, the skyline becomes both infrastructure and landscape. The rooftop is no longer a private mechanical space but a civic gateway to mobility.

II. Architecture in Motion: Designing for Aerial Mobility

The introduction of UAM forces architects to rethink form and function. Buildings will need to accommodate flight paths, wind dynamics, noise control, and passenger flow in ways previously unimaginable.

- Structural Innovation:

High-rise towers will evolve with modular platforms to support vertiports, charging stations, and lightweight canopies for noise mitigation. - Hybrid Infrastructure:

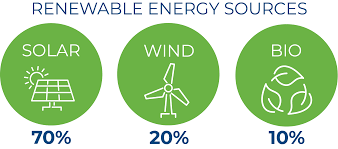

Bridges, parking decks, and logistics hubs could double as mid-air transport stations, blurring the line between architecture and vehicle. - Energy Integration:

With eVTOLs relying heavily on electric power, vertiports could serve as nodes in a city’s renewable energy grid—harvesting solar or wind energy for charging fleets.

These architectural transformations will reshape not just skylines, but also urban experience. The visual rhythm of a city filled with silent, hovering vehicles will redefine how citizens relate to the sky—turning it from a distant horizon into an animated, inhabited layer of the city.

III. Human Perception and Psychological Adaptation

Human beings evolved as ground-dwellers. Our navigation, our sense of safety, and even our social behavior are tied to the horizontal plane. Urban Air Mobility challenges this deeply ingrained habit.

The introduction of routine low-altitude flight will likely alter how people perceive proximity, privacy, and orientation.

A few key implications:

- Psychological Distance Shrinks:

Commute times collapse as aerial vehicles move point-to-point. The mental geography of cities may contract, leading to new patterns of work and leisure. - Aerial Exposure and Privacy:

As the sky becomes populated, the sense of “private verticality” disappears. People may feel observed or exposed through aerial corridors passing near windows or terraces. - Reconfigured Identity of Neighborhoods:

Areas once isolated by poor transport connections may suddenly become accessible, reshaping real estate dynamics and social hierarchies.

The shift in human perception echoes earlier transitions—such as from the horse-drawn city to the automotive metropolis—but its psychological impact will be deeper. The very definition of “up” and “down,” “inside” and “outside,” will blur.

IV. Social Stratification and Aerial Accessibility

While UAM promises efficiency, it also risks deepening social divides. In its early phase, the high costs of eVTOLs and infrastructure will likely favor affluent users, creating an “aerial elite.”

Without inclusive planning, skies could become the new highways of privilege, while those below remain bound by ground-level congestion.

Governments and planners must ensure that air mobility serves collective, not exclusive, needs. Potential strategies include:

- Public Aerial Transit Systems: integrating shared UAM services into citywide mobility networks.

- Regulated Airspace Equity: ensuring that routes do not disproportionately benefit high-income districts.

- Sustainability Incentives: linking aerial travel to green energy targets and urban decarbonization.

The key ethical question is not only who can fly, but also who benefits from the reshaping of urban geography.

V. Environmental Implications: Toward a Sustainable Sky

Contrary to fears, UAM has the potential to reduce urban emissions and lower land congestion if powered by renewable energy. However, this requires systemic design.

Sustainable UAM means:

- Full Electrification: eliminating fossil fuels from propulsion.

- Distributed Charging Infrastructure: powered by solar grids on buildings.

- Smart Air Traffic Management: optimizing flight paths to minimize noise and energy use.

Yet, sustainability goes beyond technology—it demands behavioral change. Citizens must adapt to multimodal lifestyles, balancing ground and air travel intelligently. Policymakers must set standards for airspace capacity, safety, and environmental monitoring.

If achieved, the skies above cities could become cleaner than their streets below—a paradoxical reversal of industrial-era pollution patterns.

VI. The Cultural Aesthetics of Aerial Life

Throughout history, cultural identity has been shaped by mobility: the railway age produced industrial modernity; the automobile defined suburban sprawl. UAM will inspire a new aesthetic of speed, freedom, and elevation.

Artists and designers are already exploring how flying vehicles can influence media, cinema, and architecture. The visual language of vertical mobility—gliding forms, hovering silhouettes, layered skylines—will transform advertising, tourism, and even fashion.

Meanwhile, literature and film will reinterpret the city as a dynamic “aeropolis,” suspended between earth and sky.

The future metropolis may not be dystopian, but poetic—a choreography of humans and machines sharing the air.

VII. Governance, Ethics, and the Right to the Sky

Airspace is both physical and political. Who controls it determines who moves freely.

As cities evolve, air governance will become a major arena of policy innovation. Ethical frameworks must address:

- Safety and Security: preventing collisions, hacking, and misuse.

- Privacy and Data: managing aerial sensors that collect urban imagery.

- Noise and Nuisance Management: balancing innovation with livability.

The “right to the sky” may soon be debated alongside the right to housing or clean air. Inclusive governance will require cooperation among city planners, engineers, ethicists, and citizens.

VIII. The Future of Human Connection in a Flying City

Ironically, as movement becomes effortless, social connection may grow more fragmented. Shorter commutes and private flights could reduce spontaneous public interactions—the very glue of urban life.

Designers must therefore ensure that aerial mobility complements, rather than replaces, human-centered public spaces.

Imagine vertiports integrated into mixed-use plazas, where cafés and parks coexist with flight terminals. These spaces could serve as new gathering points—bridging the gap between digital isolation and physical presence.

Ultimately, the goal is not just to move faster, but to move better—to cultivate richer, more meaningful urban encounters.

Conclusion: A New Urban Consciousness

Urban Air Mobility will not simply lift vehicles—it will lift the imagination of cities. By transcending the ground, we may rediscover what it means to inhabit space collectively.

The future metropolis will no longer be a static organism confined by streets and buildings. It will be a dynamic ecosystem of multilevel flows—of people, energy, and information.

The sky will become a civic commons, a shared domain where technology, architecture, and humanity converge.

As we stand at this threshold, the question is not whether we can build cities that fly—but whether we can build societies wise enough to share the sky.