Introduction: Intelligence as Infrastructure

In the 20th century, electricity and the internal combustion engine transformed the global economy. They became unseen infrastructure, powering industries, cities, and societies alike.

In the 21st century, Artificial Intelligence assumes a similar role. Not merely an industry or a tool, AI is becoming the backbone of productivity itself.

Unlike past technologies, AI does not just reduce labor or increase output. It reshapes the rules of economic organization, redefining the boundaries between human and machine, labor and capital, service and product.

This article examines the economic impact of AI across four dimensions: production, labor, markets, and policy, arguing that AI is not merely a technological revolution but an economic and societal transformation on a planetary scale.

1. The Transformation of Production: Smart Factories and Algorithmic Industry

1.1 From Automation to Cognition

Industrial automation has existed since the early 20th century — conveyor belts, robotic arms, and programmable logic controllers.

AI takes automation further: from executing predefined tasks to learning, optimizing, and adapting in real time.

Modern factories are becoming cognitive environments: sensors monitor equipment health, AI predicts maintenance needs, and supply chains self-optimize based on demand fluctuations.

Companies like Siemens, Foxconn, and Tesla have integrated AI systems that reduce downtime, lower energy use, and optimize production flows across continents.

1.2 The Emergence of AI-Driven Supply Chains

Global supply chains are inherently complex networks, vulnerable to disruptions. AI algorithms analyze millions of data points — shipping times, inventory levels, geopolitical events — to optimize logistics dynamically.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, AI-driven predictive logistics allowed some firms to anticipate shortages and reroute shipments, demonstrating that algorithmic resilience can outperform traditional management.

This evolution suggests that future manufacturing is as much about computation as it is about assembly. Factories, warehouses, and ports are now nodes in an intelligent, adaptive industrial web.

1.3 Industry 4.0 and Beyond

The concept of Industry 4.0 describes the integration of AI, IoT, and robotics.

But beyond the buzzword lies a structural shift: production is no longer linear but networked, modular, and programmable.

Companies that fail to adopt AI risk productivity stagnation, while early adopters leverage intelligence to achieve global scale and flexibility.

2. Labor and Human Capital: The Paradox of Automation

2.1 Job Displacement and Transformation

AI will inevitably disrupt labor markets. Routine and repetitive tasks — from data entry to quality inspection — are most at risk of automation.

According to research from McKinsey and the World Economic Forum, up to 30–40% of tasks in certain industries could be automated within two decades.

Yet the story is not purely one of displacement. AI also creates new categories of work: data labeling, model validation, AI ethics, and algorithmic auditing.

2.2 Skill Polarization and Wage Inequality

AI tends to polarize skill demand. High-skill cognitive labor that complements AI experiences growth, while low-skill routine labor declines.

Without intervention, this can exacerbate wage inequality, concentrating wealth in the hands of those controlling AI capital.

The result is a paradox: AI can boost total productivity while simultaneously widening social disparities.

2.3 Education and Reskilling for the AI Era

To mitigate these effects, education systems must pivot. Traditional curricula emphasizing memorization must give way to problem-solving, critical thinking, and digital literacy.

Reskilling initiatives — government-led or corporate — are critical. For example:

- Amazon’s upskilling programs train warehouse workers in AI-augmented roles.

- Singapore’s SkillsFuture initiative provides lifelong learning credits for tech adaptation.

Without proactive human capital strategies, AI-driven economies risk structural unemployment and social unrest.

3. AI as an Economic Multiplier

3.1 Productivity Gains Across Sectors

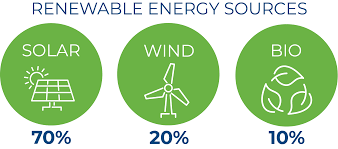

AI is not limited to manufacturing; its impact spans finance, healthcare, retail, energy, and logistics.

- Finance: AI improves risk assessment, fraud detection, and algorithmic trading efficiency.

- Healthcare: Diagnostic AI can detect diseases earlier, personalize treatment plans, and optimize hospital operations.

- Retail: AI personalizes marketing, forecasts demand, and manages inventory.

Across these sectors, AI compresses decision-making cycles, increases throughput, and reduces errors, acting as an economic force multiplier.

3.2 The Scale of Economic Impact

Estimates suggest AI could add $15–30 trillion to global GDP by 2035 (PwC, 2023).

Yet these gains will not be evenly distributed. Countries that lead in AI research, infrastructure, and adoption — currently the U.S., China, and select EU nations — will capture disproportionate benefits.

This raises geopolitical questions: if AI is productivity infrastructure, then AI sovereignty equals economic sovereignty.

3.3 New Business Models

AI enables novel economic structures:

- Algorithm-as-a-Service: firms sell predictive or generative intelligence rather than physical products.

- Dynamic Pricing and Microtransactions: real-time optimization maximizes revenue and minimizes waste.

- Peer-to-Peer Intelligent Platforms: decentralized marketplaces (e.g., AI-driven energy trading or micro-logistics) reshape value creation.

The common thread: information and intelligence become central assets, challenging traditional notions of labor and capital.

4. Markets, Competition, and the Concentration of Power

4.1 Winner-Takes-Most Dynamics

AI is inherently scalable and networked. Once trained on large datasets, models can be deployed globally at minimal marginal cost.

This creates “winner-takes-most” dynamics, where leading firms dominate markets by controlling the best data, talent, and computing infrastructure.

Examples:

- OpenAI and Google DeepMind dominate cutting-edge generative AI research.

- Amazon, Alibaba, and Microsoft control cloud infrastructure essential for model training.

Without regulation, AI could entrench monopolistic power, challenging traditional competitive markets.

4.2 The Data Economy and Tradeoffs

Data is the new oil — raw input that fuels intelligence. Control over datasets translates into economic leverage.

Yet data markets raise privacy, fairness, and ethical dilemmas: how do we balance AI productivity with individual rights?

Governments now face a dual task: fostering innovation while preventing monopolistic capture of knowledge. Policies such as the EU AI Act and U.S. Federal Trade Commission guidelines attempt to address these challenges, but global coherence remains elusive.

5. International Competition and Geopolitics of AI

5.1 Strategic Technology Competition

AI is not only an economic driver but a geopolitical tool. Nations compete to dominate AI in:

- Defense and cybersecurity

- Intelligence analysis

- Industrial productivity

China’s Next Generation AI Development Plan and the U.S. AI Initiative exemplify strategic competition. Leadership in AI is now synonymous with national competitiveness and technological sovereignty.

5.2 Global Coordination vs. Fragmentation

While competition is inevitable, uncoordinated deployment could lead to fragmented AI standards, ethical inconsistencies, and cross-border security risks.

International collaboration in AI safety, standardization, and open research is critical to avoid a fractured digital economy.

5.3 Development Gap and Inclusion

Developing nations risk being left behind in the AI revolution due to lack of infrastructure, talent, or capital.

Bridging this gap is both an economic and moral imperative. Global initiatives — technology transfer, open-source models, and AI literacy programs — are essential to ensure inclusive growth.

6. Policy and Regulation: Governing the AI Economy

6.1 Ethical and Economic Regulation

AI policy must balance innovation, productivity, and social equity.

Key levers include:

- Antitrust oversight to prevent monopolization

- Data governance to protect privacy and enable equitable access

- Taxation frameworks that capture value from automated production

- Labor policies that fund reskilling and social protection

The challenge: regulation must be flexible enough to adapt to rapid technological change yet robust enough to enforce fairness.

6.2 Incentives for Responsible Innovation

Policymakers can shape AI deployment through incentives:

- Grants for open models and AI commons

- Tax breaks for ethical AI integration

- Subsidies for small businesses adopting AI responsibly

These policies encourage both economic growth and ethical compliance, ensuring AI serves society rather than narrow corporate interests.

6.3 International Standards and AI Governance

AI’s global nature demands international agreements:

- Standards for safety and reliability

- Protocols for cross-border data flows

- Cooperative R&D initiatives

Without coordination, the economic benefits of AI may remain concentrated, while risks — bias, cybersecurity threats, and automation shocks — remain global.

7. The Future of Work: AI as a Partner, Not a Replacement

7.1 Collaborative Intelligence

Rather than replacing humans wholesale, AI is best viewed as a collaborative partner.

Hybrid teams, where humans supervise and augment AI outputs, outperform either working alone. Examples:

- AI-assisted radiology diagnoses

- Algorithmic legal research with lawyer oversight

- Generative design tools in architecture

This collaboration magnifies productivity while retaining human judgment and creativity.

7.2 Redefining Employment and Value

In AI-driven economies, employment may become task-based rather than job-based.

Humans focus on strategic, creative, and relational tasks, while machines handle repetitive, data-intensive functions.

Economic value shifts from production quantity to quality, interpretation, and oversight. In this sense, AI transforms the meaning of work itself.

7.3 Societal Adaptation

Societies must adapt to a future where income and social structures are increasingly decoupled from traditional employment. Policies such as universal basic income (UBI), wealth redistribution, and social dividends from AI-generated value may become necessary to maintain stability.

Conclusion: Intelligence as Economic Infrastructure

Artificial Intelligence is more than a tool; it is the invisible architecture of the global economy.

It multiplies productivity, transforms labor, redistributes value, and redefines markets. Yet it also concentrates power, creates new inequalities, and challenges governance frameworks.

The central challenge of the AI economy is balance: maximizing innovation while preserving equity, scaling efficiency while maintaining human agency, and leveraging intelligence while safeguarding freedom.

The nations, firms, and communities that succeed will not be those that build the most powerful AI, but those that integrate AI into human-centered systems, creating economies that are both productive and ethical.

In this new era, intelligence itself becomes a resource — a form of economic infrastructure as vital as roads, power grids, and financial networks. And like all infrastructure, it must be designed, maintained, and shared responsibly to ensure the prosperity of civilization as a whole.