Introduction: The Invisible Engine of Change

When people think of climate change, they often picture melting glaciers, rising seas, or greenhouse gas charts. Yet beneath the scientific data and policy negotiations lies something more subtle but equally powerful — culture.

Culture shapes how we understand nature, what we value, how we consume, and how we act. The climate crisis, therefore, is not only an environmental or technological challenge but also a cultural one. To truly achieve sustainability, humanity must undergo a transformation in beliefs, habits, and collective imagination — becoming a climate-conscious society.

This essay explores how culture, values, and social norms can drive or hinder climate action, the role of education and media in shifting perceptions, and how art, storytelling, and community life can inspire global change from the bottom up.

1. Climate Change as a Cultural Problem

1.1 The Dominant Worldview: Human over Nature

For centuries, industrial civilization has been guided by an anthropocentric worldview — the belief that humans stand apart from and above nature. This has produced progress and prosperity but also environmental destruction. Nature became a resource to be extracted, not a partner to coexist with.

This cultural mindset — of domination, convenience, and consumerism — underlies the climate crisis. It leads to overconsumption, waste, and denial of ecological limits. Solving the climate crisis therefore requires more than policies or technologies; it requires rethinking who we are in relation to the planet.

1.2 The Cultural Lag

Sociologist William Ogburn coined the term “cultural lag” to describe how values and social institutions often evolve slower than technological change. Humanity has developed tools to alter the climate but lacks the cultural maturity to manage that power responsibly. Bridging this gap — aligning our culture with planetary boundaries — is perhaps the greatest task of our time.

2. From Awareness to Consciousness

2.1 Information Is Not Enough

Despite decades of awareness campaigns, public concern does not always translate into sustained action. Knowledge alone cannot overcome habits shaped by culture — habits of consumption, convenience, and comfort.

A climate-conscious society requires more than awareness; it demands consciousness — a deep internalization of planetary ethics that influences daily choices and collective institutions.

2.2 The Psychology of Denial

Cultural psychologists note that humans have psychological defenses against overwhelming threats. Climate change, being abstract and global, triggers cognitive dissonance, denial, or moral disengagement. We rationalize our inaction (“others will fix it”) or depoliticize the issue (“it’s just weather”).

Breaking these defenses requires narratives of hope and agency — not guilt or doom. People act when they believe their actions matter and when they see others doing the same.

3. Education for Planetary Citizenship

3.1 Redefining Education

Traditional education prepares students for economic productivity, not planetary stewardship. To cultivate a climate-conscious generation, we need education for ecological literacy — teaching how energy, ecosystems, and human systems interconnect.

Programs like Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) by UNESCO emphasize critical thinking, empathy, and interdisciplinary understanding. Students learn not just facts about climate change, but how to live sustainably within their communities.

3.2 Experiential Learning

Field-based and project-based learning helps bridge theory and action. School gardens, citizen science, or local conservation projects transform abstract issues into tangible experiences. When young people plant trees, measure carbon footprints, or design recycling systems, climate responsibility becomes personal.

3.3 The Role of Universities

Universities are incubators for social innovation. Initiatives such as carbon-neutral campuses, climate labs, and green entrepreneurship programs demonstrate that institutions can model sustainability while educating future leaders.

4. The Media: Mirror, Messenger, and Mobilizer

4.1 Media Narratives and Climate Framing

Media is a cultural mirror — it shapes public discourse and collective imagination. The way climate stories are framed can either inspire change or deepen apathy. For years, climate coverage was dominated by scientific jargon and catastrophic imagery, alienating audiences.

Today, effective storytelling emphasizes solutions, community resilience, and shared benefits. Outlets like The Guardian’s climate section or National Geographic’s documentaries show that compelling narratives can reframe climate change from a remote threat into a lived human story.

4.2 Social Media and Youth Activism

Digital platforms have empowered new forms of climate communication. Movements like Fridays for Future, #StopEACOP, and Extinction Rebellion have mobilized millions through hashtags, viral videos, and global strikes.

Social media democratizes advocacy but also risks polarization and misinformation. Building a climate-conscious digital culture means combining passion with credibility, emotion with evidence.

4.3 Entertainment as Education

Films, games, and art can translate complex ideas into emotional experiences. Pixar’s WALL·E, Bong Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer, or Netflix’s Don’t Look Up all dramatize humanity’s environmental blind spots. Such works invite reflection, empathy, and dialogue — key ingredients of cultural transformation.

5. The Role of Art and Imagination

5.1 Art as Empathy Engine

Art can move people where data cannot. Climate art — from large-scale installations like Olafur Eliasson’s Ice Watch to community murals — gives the crisis a human face and a sensory reality. Art activates empathy, turning abstract statistics into emotional truth.

5.2 The Power of Storytelling

Throughout history, stories have guided moral imagination. Climate storytelling connects individual experience with planetary change — from indigenous myths of Earth balance to speculative fiction envisioning sustainable futures.

Authors like Kim Stanley Robinson, in The Ministry for the Future, use narrative to explore governance, ethics, and collective survival. Such works invite us to imagine the world we want to live in, not just the one we fear losing.

5.3 The Rise of Eco-Aesthetics

A new aesthetic movement — eco-aesthetics — celebrates the beauty of sustainability. Architecture, design, and fashion are shifting toward natural materials, circularity, and biophilic design. Beauty, when aligned with ecology, becomes a cultural language for sustainability.

6. The Ethics of Everyday Life

6.1 From Consumer to Citizen

The transformation toward a climate-conscious culture begins with redefining identity. In industrial society, we are trained to be consumers; in a sustainable society, we must become citizens — participants in the collective management of the planet.

This shift involves re-evaluating success not in terms of accumulation but contribution, not possession but participation.

6.2 Lifestyle as Politics

Personal choices — food, travel, fashion, energy — are not private acts but political statements. The rise of minimalism, plant-based diets, and slow fashion reflects new cultural values emphasizing moderation, connection, and ethics.

However, individual change must complement systemic reform. Culture is powerful when it shapes both citizens’ habits and institutions’ priorities.

6.3 The Role of Ritual and Community

Cultural change is sustained through ritual — repeated symbolic acts that express shared values. Community gardens, local repair cafés, or annual “Earth Day festivals” serve as modern eco-rituals that reinforce belonging and responsibility.

When sustainability becomes a social norm — something expected, celebrated, and rewarded — transformation becomes self-sustaining.

7. Indigenous Wisdom and Ecological Knowledge

7.1 Learning from Traditional Cultures

Indigenous communities have long practiced forms of sustainable living based on reciprocity and respect for nature. The Māori concept of kaitiakitanga (guardianship), or the Andean sumak kawsay (good living), embodies balance rather than exploitation.

These traditions remind modern societies that sustainability is not a new invention but an ancient wisdom disrupted by industrial modernity.

7.2 Integrating Knowledge Systems

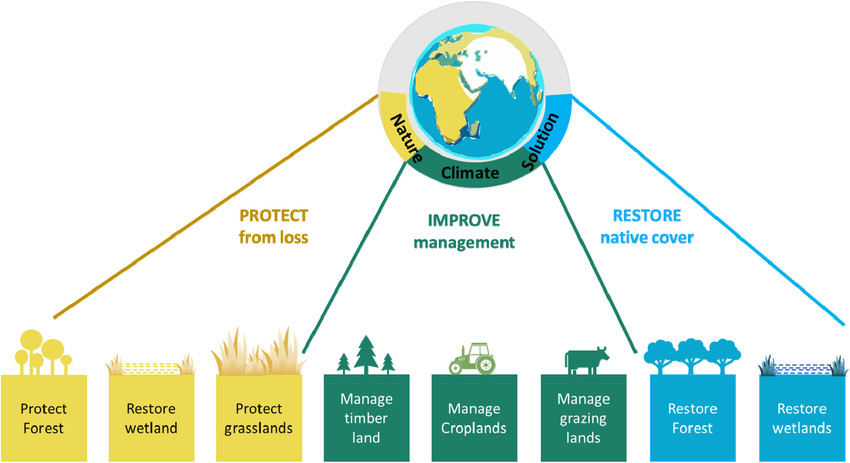

Integrating indigenous and scientific knowledge can improve conservation and adaptation strategies. For example, Aboriginal fire management in Australia or Inuit sea-ice monitoring in the Arctic combines local expertise with modern tools to enhance resilience.

7.3 Decolonizing Climate Culture

Climate justice also means decolonizing environmentalism — recognizing how colonial histories and extractive economies created both cultural and ecological damage. A truly climate-conscious culture values plurality, equity, and humility in its relationship to the planet.

8. The Economy of Meaning: Green Values in Business

8.1 Beyond Growth: Toward Regenerative Economies

Culture shapes economics as much as economics shapes culture. The dominant economic story — infinite growth on a finite planet — is culturally unsustainable. New paradigms like the circular economy, doughnut economics, and regenerative capitalism redefine prosperity as balance and restoration.

8.2 Corporate Culture and Responsibility

Companies are cultural actors. When corporations embrace sustainability authentically — not as branding, but as purpose — they influence employees, consumers, and competitors.

Patagonia’s decision to donate profits to environmental causes or Interface’s “Mission Zero” campaign demonstrates how corporate culture can drive systemic change.

8.3 The Green Consumer Revolution

Consumer culture is shifting toward ethics and transparency. Certifications like Fair Trade, B Corp, and Carbon Neutral are now symbols of social trust. When ethical consumption becomes a status symbol, culture aligns with sustainability.

9. Religion, Philosophy, and Moral Renewal

9.1 Faith Traditions and Stewardship

All major religions contain ecological ethics. Christianity’s idea of stewardship, Islam’s khalifa (trusteeship), Buddhism’s interdependence, and Indigenous spirituality’s reverence for land all point toward a moral duty to protect creation.

Faith-based organizations now play growing roles in mobilizing communities for climate justice — from the Laudato Si’ movement in Catholicism to Islamic climate declarations.

9.2 Secular Ethics of Care

Even beyond religion, an ethical awakening is emerging: recognizing that caring for the planet is an expression of care for each other. Environmentalism becomes not ideology but empathy — a shared moral horizon for humanity.

10. Youth and Intergenerational Transformation

10.1 The Generation of Climate Consciousness

Young people today are the first generation to grow up fully aware of the climate crisis — and the last with time to prevent its worst effects. This awareness has fostered a new civic identity centered on intergenerational justice.

Movements led by youth — from Greta Thunberg to Pacific Island activists — remind older generations that climate inaction is a form of moral neglect.

10.2 Education Meets Activism

Education systems increasingly integrate activism and sustainability. Student-led campaigns for fossil fuel divestment or zero-waste campuses exemplify how learning and action can merge into cultural transformation.

10.3 Hope as a Practice

For youth movements, hope is not optimism but discipline — the choice to act even without guarantees. This moral resilience defines the emerging culture of climate consciousness.

11. Building the Culture of the Future

11.1 From Fear to Vision

Fear can awaken but not sustain change. A climate-conscious culture must be rooted in vision — in imagining futures of abundance within limits, community within diversity, technology in harmony with life.

Designers, educators, and leaders must create spaces of possibility — from eco-cities to climate-positive lifestyles — that show sustainability can be aspirational, not sacrificial.

11.2 The Narrative Shift

The old story: humans vs. nature.

The new story: humans as part of nature.

When societies rewrite their foundational narrative, everything else — economy, policy, lifestyle — follows. The future of climate action depends on this narrative revolution.

11.3 Culture as Infrastructure

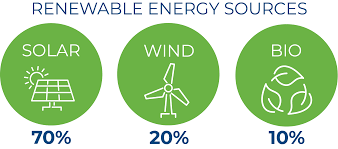

Policies and technologies may build solar farms and electric cars, but culture builds meaning. A truly resilient civilization will have sustainability embedded in its identity, not just its infrastructure.

Conclusion: The Regeneration of Humanity

The path to a sustainable future runs not only through laboratories and parliaments but through hearts, minds, and shared imagination. Cultural transformation is the invisible infrastructure of climate solutions.

A climate-conscious society is one that lives within limits, celebrates interdependence, and finds joy in stewardship rather than consumption. It is a civilization that measures progress not by GDP, but by the health of its ecosystems and the happiness of its people.

If we can transform our culture, we can transform everything else — because every system we build, every policy we write, every economy we design reflects the stories we tell about who we are.

The climate crisis is ultimately a crisis of meaning — and the solution is a cultural renaissance that reconnects humanity with the living Earth. When that happens, sustainability will cease to be a choice and become a way of life — the natural expression of a mature civilization.