Introduction: Beyond the Screen

For much of computing history, interaction has been mediated through flat surfaces: keyboards, mice, and touchscreens. These interfaces, while functional, are fundamentally symbolic—they translate the messy richness of human experience into clicks, commands, and codes.

But as technology becomes more immersive, responsive, and perceptually intelligent, a new paradigm is emerging—embodied interaction, where the human body and machine perception merge into a shared sensory field.

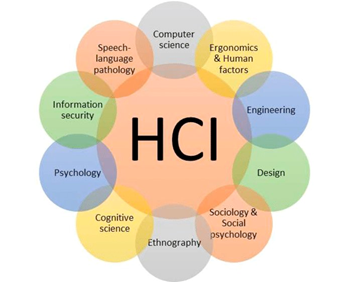

This shift is not just technological; it is philosophical. It redefines what it means to “interact.” Instead of manipulating objects on a screen, users inhabit a space where digital and physical realities blend. Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), haptics, voice, gesture, and neural interfaces are transforming human–computer interaction (HCI) from symbolic to somatic—from thought to touch.

The age of embodied computing is the age of presence.

1. From Abstract Commands to Lived Experience

Early computers required humans to adapt to machines. Command-line interfaces demanded technical literacy, memorization, and abstraction. As interfaces evolved—from graphical desktops to multitouch screens—they grew more intuitive, aligning with human perception.

Yet even touchscreens are limited: they flatten depth, texture, and emotion into two dimensions. The next stage of HCI seeks to restore embodiment—to return the human body as a full participant in interaction, not just a finger on glass.

Embodied interaction, a term popularized by Paul Dourish, posits that meaning arises not from detached symbols but from situated, bodily experience. We understand the world by doing, not just thinking. Thus, interfaces that engage our senses—sight, sound, motion, touch—tap into deeper layers of cognition.

In this paradigm, the computer becomes less an object and more an environment.

2. The Rise of Immersive Technologies

Virtual and Augmented Reality technologies exemplify this new embodied mode. They collapse the divide between input and output, creating environments where users act rather than command.

- Virtual Reality (VR) immerses users in fully simulated spaces, enabling training, exploration, or therapy through experience rather than description.

- Augmented Reality (AR) overlays digital information onto physical space, merging perception with computation.

- Mixed Reality (MR) allows physical and virtual elements to coexist and interact dynamically.

These technologies reimagine presence—not as being in front of a computer, but within computation itself.

When an architect walks through a 3D model before construction, or a surgeon rehearses a procedure in a simulated body, the interface ceases to be an intermediary; it becomes the world itself.

3. The Body as Interface

In embodied computing, the human body becomes both input and output. Sensors track movement, biometrics, and even neural signals; actuators provide haptic feedback or motion cues.

This convergence gives rise to a new kind of dialogue between body and machine—one based on rhythm, sensation, and gesture.

3.1 Motion as Language

Gesture recognition systems, from Microsoft Kinect to AI-based computer vision, interpret bodily movement as communicative acts.

In dance or sports training, these systems analyze form and provide feedback. In accessibility design, gesture control enables interaction without touch—crucial for users with mobility impairments.

The body thus becomes expressive, its movements translating directly into digital meaning.

3.2 Touch as Truth

Haptic feedback—vibrations, resistance, or temperature—restores tactility to the digital. In VR surgery, surgeons feel the “give” of tissue; in gaming, players feel the recoil of virtual impact.

Touch grounds virtuality—it reminds us that embodiment is not optional, but essential to experience.

3.3 Neural Interfaces: The Mind Extends

Brain–Computer Interfaces (BCIs) push embodiment to its limit. By decoding neural signals, BCIs allow users to control devices through thought alone.

Companies like Neuralink and OpenBCI envision futures where prosthetics, computers, or even entire environments respond directly to neural activity.

When the boundary between intention and interaction disappears, the interface becomes invisible—and the human–machine divide collapses.

4. Designing for the Senses

Embodied interaction requires a rethinking of design principles. Traditional HCI relied on clarity and simplicity; embodied HCI demands sensory orchestration.

Each sense offers a unique channel of cognition:

- Sight provides spatial orientation and pattern recognition.

- Sound conveys emotion and urgency.

- Touch gives feedback and realism.

- Motion expresses agency and rhythm.

- Balance and proprioception provide immersion and comfort.

Effective design integrates these senses without overwhelming the user. For instance, in VR environments, mismatched sensory cues (visual motion without physical movement) cause cybersickness. Thus, embodied design must align perception and action harmoniously—a form of digital ergonomics.

This sensory integration is not only technical but aesthetic. The goal is to craft experiences that feel natural, meaningful, and emotionally resonant.

5. The Philosophy of Presence

Presence—the feeling of “being there”—is the holy grail of immersive interaction.

Philosophically, presence arises when the brain’s predictive models of reality are satisfied by sensory input, whether that input is physical or simulated. When VR deceives the senses convincingly, users respond as if virtual events were real.

Yet presence is not merely sensory; it is existential. The philosopher Merleau-Ponty argued that perception is not the brain observing the body, but the body experiencing the world.

Embodied interaction thus reclaims the body’s centrality in cognition—machines no longer stand apart from human experience but participate in it.

In this view, future HCI is not about better screens, but richer being.

6. The Ethics of Embodiment

As machines penetrate deeper into our bodies and minds, embodiment introduces profound ethical questions.

- Privacy of the body: Motion data, biometric signals, and neural patterns reveal intimate aspects of identity.

- Consent and control: When the body becomes an interface, where does user agency end? Can systems manipulate posture, emotion, or decision-making unconsciously?

- Psychological integrity: Extended immersion can blur boundaries between real and simulated selves, raising questions about addiction, dissociation, or emotional conditioning.

Designers must approach embodied systems with ethical humility. The body is not a datapoint; it is the site of personhood.

Embodied ethics must protect the dignity of experience—the right to one’s sensations, emotions, and presence.

7. Embodied Learning and Empathy

One of the most transformative applications of embodied interaction lies in education and empathy-building.

VR enables experiential learning—students can explore ancient cities, practice surgery, or witness climate change in real time. Such experiences engage not just cognition but emotion and memory, deepening understanding.

Empathy research shows that perspective-taking through VR (e.g., embodying a refugee, a person with a disability, or another gender) can shift attitudes more effectively than reading or discussion.

By engaging the body, technology reaches the moral imagination.

However, “empathy simulation” must be designed with care. Temporary embodiment does not equal lived experience. Ethical education through VR requires reflection, context, and critical framing—otherwise, it risks trivializing real suffering.

8. Cultural and Aesthetic Dimensions

Embodied interaction is not culturally neutral. Different societies interpret gesture, gaze, and personal space differently.

A nod may signify agreement in one culture, neutrality in another. Designers must localize sensory metaphors, ensuring embodied systems respect cultural diversity.

Aesthetically, embodied HCI opens new frontiers in art and storytelling. Immersive theatre, interactive installations, and sensory narratives blur the line between participant and creator.

The artist becomes a world-builder; the viewer becomes the medium.

Such experiences invite us to feel technology not as cold machinery but as a living extension of imagination.

9. The Future: Human–Machine Symbiosis

As embodiment deepens, we approach an era of symbiotic interaction—a partnership between human intuition and machine perception.

- AI interprets sensory data at scales beyond human capacity.

- Humans provide context, creativity, and empathy.

- Together, they co-construct environments responsive to both cognition and emotion.

Consider adaptive spaces that adjust lighting, temperature, or sound based on mood; wearable systems that translate biometric states into music; or collaborative robots that anticipate motion through shared perception.

Such symbiosis transforms computing from tool-use into co-presence.

The future interface will not be used—it will be lived.

10. Conclusion: The Human Body as the Final Frontier

The story of HCI has always been about narrowing the gap between human intention and machine response.

Embodied interaction is its culmination—a return to the truth that technology is, at its core, an extension of the body and mind.

Yet this future demands humility. To design for embodiment is to design for the self.

We must protect the sanctity of sensation, the right to mental privacy, and the freedom of presence.

When the screen dissolves and the world itself becomes the interface, we face a profound question:

Will technology bring us closer to reality—or replace it with something more seductive, yet less human?

The answer will depend not on how powerful our machines become, but on how wisely we inhabit them.