Introduction: From Roads to the Sky – The Next Economic Frontier

Cities have always evolved in response to the ways humans move. From the horse-drawn carriage to the electric vehicle, each transportation revolution has reshaped urban economies — creating new industries, redefining real estate value, and transforming patterns of labor and consumption. Now, as the world approaches the era of Urban Air Mobility (UAM), we are witnessing the emergence of what some economists call the “aerial economy” — a new layer of economic activity enabled by electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft, autonomous drones, and low-altitude airspace infrastructure.

UAM is more than just a transportation innovation. It represents a new economic ecosystem that merges aerospace, data infrastructure, artificial intelligence, and green energy. The implications reach far beyond faster travel; they encompass new supply chains, industries, and investment paradigms. This article examines how UAM could reshape urban economies — from labor markets to energy grids — and what opportunities and risks lie ahead as cities prepare to integrate the “sky layer” into their economic fabric.

1. The Birth of the Aerial Economy

1.1 A New Industrial Ecosystem

The development of UAM is giving rise to a distinct economic system that interlinks multiple sectors:

- Aerospace and engineering, for the design and production of eVTOLs and air traffic systems.

- Digital infrastructure, including cloud-based traffic management and AI algorithms for autonomous flight.

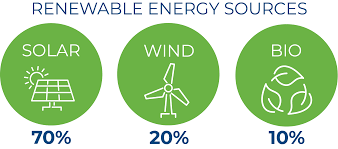

- Energy and charging networks, as eVTOLs require high-capacity electric grids and renewable energy sources.

- Construction and urban design, for vertiport planning and integration with existing transportation hubs.

- Services and logistics, encompassing everything from maintenance to aerial deliveries.

According to Morgan Stanley’s projection, the global UAM market could reach $1 trillion by 2040, driven by passenger transport, logistics, infrastructure, and digital services. China, the United States, and Europe are expected to lead the field, supported by massive investments from both government and private capital.

1.2 The Rise of “Low-Altitude Economy” in China

China’s “low-altitude economy” (低空经济) policy reflects a national strategy to capitalize on this emerging frontier. Provinces such as Guangdong, Hunan, and Zhejiang have launched pilot zones for drone logistics, aerial sightseeing, and short-range eVTOL transport. The goal is not merely to develop technology but to build a complete economic chain — from aircraft manufacturing and software development to service operations and data platforms.

In Shenzhen, EHang and AutoFlight are pioneering aerial tourism and logistics routes, while local governments plan to connect these networks with existing subway and highway systems. This integration is already attracting venture capital, creating high-tech jobs, and promoting regional economic clustering.

2. Economic Impacts on Urban Infrastructure and Real Estate

2.1 Reimagining Urban Space

UAM will fundamentally alter how urban space is valued and used. Traditional transport infrastructure — highways, subways, bus lines — has long dictated real estate prices and commercial zoning. With vertical mobility, proximity to “vertiports” could become the new measure of urban accessibility.

For example:

- Residential properties near aerial hubs could gain significant value, similar to those near metro stations in the 20th century.

- Commercial districts might develop around rooftop vertiports and logistics terminals.

- Peripheral areas could benefit from improved connectivity, easing urban congestion and decentralizing employment.

Architects and city planners are already exploring “vertical zoning” — designing buildings that integrate aerial landing pads, charging stations, and passenger terminals on upper floors. This could lead to the rise of “3D cities” where economic activity occurs across multiple layers: underground, ground level, and the sky.

2.2 Real Estate and Investment Opportunities

Real estate developers are taking notice. Goldman Sachs has noted that air mobility infrastructure will create a new class of “aerial real estate.” Buildings that support UAM services could command premium rents and attract luxury retail and hospitality investments.

In Asia, companies like Hyundai’s Supernal, Volocopter, and XPENG AEROHT are partnering with property firms to plan integrated air mobility hubs within mixed-use developments. These hubs are not just transportation nodes but economic catalysts, generating new consumer experiences — from sky restaurants to aerial commuting services.

3. Labor Markets and Workforce Transformation

3.1 New Jobs, New Skills

As with previous technological shifts, UAM will disrupt existing labor markets while creating new ones. Key emerging roles include:

- eVTOL engineers and maintenance technicians

- Airspace traffic data analysts

- Urban air logistics coordinators

- Battery recycling and energy systems specialists

- AI safety and ethics managers

In the early stages, UAM will demand high-skill labor concentrated in engineering and data science. But as adoption grows, the service economy will expand — including pilots (in semi-autonomous phases), ground staff, infrastructure operators, and customer experience designers.

3.2 The Automation Paradox

Autonomy will eventually reduce human control requirements. AI-driven flight management could eliminate many manual operations, leading to potential job displacement in traditional aviation sectors. However, automation will also create new cognitive jobs — requiring workers who can oversee complex systems, interpret real-time analytics, and ensure safety compliance.

Governments must invest in reskilling programs to ensure that workers in traditional logistics or aviation can transition into UAM-related roles. This aligns with global trends toward “Industry 5.0,” where human creativity complements automation rather than competes with it.

4. Green Growth and Energy Economics

4.1 Sustainable Energy Integration

One of UAM’s most compelling promises is its potential to accelerate the green energy transition. eVTOLs are powered by electricity, meaning their carbon footprint depends largely on how clean the grid is. The expansion of UAM thus creates an economic incentive for renewable energy investment.

Cities aiming to deploy UAM at scale must expand their charging infrastructure and integrate smart-grid technology capable of balancing high energy demand. Hydrogen fuel cells and solid-state batteries could redefine both aviation and urban energy markets.

4.2 Life Cycle and Environmental Costs

However, sustainability is not guaranteed. The production and disposal of batteries, as well as the construction of new infrastructure, generate emissions. Economists emphasize the importance of life cycle assessment (LCA) to evaluate UAM’s total ecological footprint — from manufacturing to recycling.

Emerging circular economy models propose that used eVTOL batteries could be repurposed for grid storage or micro-energy systems, turning potential waste into value. This synergy between air mobility and green energy systems marks one of the most promising intersections of industrial innovation.

5. UAM and the Data-Driven Economy

5.1 Data as the New Currency of the Sky

UAM systems generate massive volumes of data — on flight patterns, weather conditions, energy usage, and passenger behavior. Managing this data securely and efficiently is both a challenge and an opportunity.

Private companies could leverage aerial data for:

- Urban planning and traffic optimization

- Environmental monitoring

- Targeted services and advertisements

- Predictive maintenance and insurance pricing

In essence, data will become the fuel of the aerial economy, powering decision-making and generating new forms of digital value.

5.2 Risks of Data Monopoly and Surveillance

The economic benefits of aerial data come with risks. Without robust data governance, a few large corporations could monopolize urban airspace information, leading to unequal access and potential surveillance concerns.

To prevent this, policymakers should promote open data ecosystems — ensuring that critical UAM data (such as weather and routing information) remains publicly accessible while protecting personal and commercial privacy.

6. The Global Economic Landscape: Competition and Collaboration

6.1 The U.S. and Europe: Innovation and Regulation

In the U.S., NASA’s AAM initiative and the FAA’s evolving certification frameworks have positioned the country as a leader in innovation. Silicon Valley startups like Joby Aviation and Archer are backed by major investors, while cities like Los Angeles and Miami are planning early adoption routes.

Europe, in contrast, emphasizes regulation and sustainability. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) enforces strict safety and environmental standards, pushing for cross-border harmonization. Paris and Munich are at the forefront of integrating air taxis into public transport systems.

6.2 China: State-Led Coordination

China’s state-driven model gives it a unique advantage in rapid deployment. The government’s “low-altitude economy” strategy unifies R&D, infrastructure, and policy across multiple regions. Public–private partnerships ensure both innovation and scalability. Shenzhen and Guangzhou are expected to become global leaders in commercial UAM operations before 2030.

6.3 Emerging Markets: Leapfrogging Opportunities

In developing regions — particularly Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America — UAM offers potential to bypass outdated infrastructure. Remote areas lacking highways or railways could gain rapid access to urban centers. This “leapfrog effect” mirrors how mobile phones transformed connectivity in the early 2000s.

7. The Urban Economy of the Future: Beyond Transportation

7.1 Integration with Smart Cities

UAM fits naturally into the smart city paradigm, where digital infrastructure coordinates mobility, energy, and governance. The synergy between aerial networks, IoT sensors, and AI decision systems could unlock unprecedented urban efficiency.

Imagine cities where:

- Real-time aerial routes adjust to weather and congestion.

- Drones deliver medical supplies during emergencies.

- Autonomous eVTOLs shuttle passengers between rooftops connected by smart logistics systems.

This interconnected ecosystem blurs the line between physical and digital economies.

7.2 Tourism, Retail, and Experience Economy

The rise of the aerial economy will also transform tourism and entertainment. Aerial sightseeing, sky dining, and drone-based event displays are already becoming profitable niches. Luxury brands may sponsor exclusive air routes, while cities could monetize airspace for marketing or cultural experiences.

In this sense, UAM doesn’t just move people — it creates experiences, fueling an entirely new branch of the experience economy.

8. Challenges and Economic Risks

8.1 Capital and Market Uncertainty

Despite optimism, UAM remains capital-intensive. High initial costs for R&D, certification, and infrastructure could slow adoption. Investors face uncertainty over demand, regulatory approval, and technological reliability.

8.2 Inequality and Accessibility

As discussed in previous analyses, early UAM services will likely cater to high-income groups. Without deliberate policy measures — such as subsidies, shared models, and integration with public transport — the aerial economy could exacerbate urban inequality.

8.3 Regulatory Bottlenecks

Complex airspace regulations remain one of the biggest barriers. Delays in certification or inconsistent international standards could limit cross-border scalability, slowing the emergence of a unified global market.

Conclusion: The Sky as the Next Economic Domain

Urban Air Mobility is poised to redefine not only transportation but the very structure of urban economies. By merging aerospace technology, green energy, and digital infrastructure, it represents the next great transformation in urban capitalism — one that extends economic activity into the vertical dimension.

If managed wisely, UAM can stimulate innovation, reduce congestion, and drive sustainable growth. Yet the economic benefits will depend on how equitably this new domain is governed. The sky, like the internet before it, must remain an open and shared resource — not a playground for the privileged few.

The aerial economy challenges cities to rethink fundamental questions:

Who owns the sky? Who profits from it? And how can we ensure that the economic ascent into the air also uplifts those on the ground?

The answers will determine whether UAM becomes a symbol of progress — or a new frontier of inequality.